Eyes on the steppe: Volunteering for the manul cause

How you can help researchers uncover the hidden lives of manuls

As I mentioned last week, the Manul Working Group is doing some amazing work to study and conserve manuls and their natural habitats! Their efforts are so impactful that I've proudly sent 40% of the subscription revenue from the first ~2 months of this Substack their way, totaling $238.06 (another big thank-you to the paid subscribers who made this happen!). Every contribution helps expand their vital network of camera traps and funds additional research and conservation initiatives (more exciting news on those soon!).

In my previous article, I briefly mentioned the Manul Working Group’s need for volunteers to sort through terabytes of camera trap data. Let’s face it — sorting thousands upon thousands of images can be tedious and daunting, far beyond what any single person could reasonably manage alone. That’s precisely why they need your help. Yes, this is your chance to help — sorting images and identifying animals, providing the data that will directly contribute to the understanding of manul populations over the long term.

Why is this important? Well, manul populations can fluctuate dramatically, even within relatively short periods. Simple snapshot data from one or two years just isn’t sufficient to capture the full story. Long-term monitoring — think decades, not years — is essential for accurately gauging population health, vulnerability, and ecosystem changes. This approach helps pinpoint areas of greatest conservation concern and understand the dynamics between manuls, their prey, and predators sharing their habitats.

Currently, the Manul Working Group has a huge volume of camera trap images from the Altai Mountains, provided by Sergey Spitsyn (Altai Nature Reserve) and the volunteer expedition “In the footsteps of the snow leopard”. These images were taken in some of the most remote and dramatic high-mountain landscapes of the region, and they offer a rare view into this ecosystem. Interestingly, camera trap networks designed initially for other animals, like snow leopards often yield valuable insights into other species, including our beloved manuls, but also species like rodents and birds. It’s an ecological treasure trove just waiting to be explored!

So, what exactly does volunteering look like, and why am I enthusiastically contributing my time? Let me walk you through it:

Volunteers receive clear, step-by-step instructions on how the sorting process works. For those who are comfortable with it, there’s also an option to use R, a free programming language often used by biologists, to help organize and map images more efficiently. But don’t worry, using R is entirely optional. The overall task is simple: carefully examine each image for signs of animal life and sort them accordingly.

Camera traps typically capture images in quick succession when triggered, often generating sets of three or more nearly identical photos. It's your task to discern subtle movements or camouflaged animals. Trust me, having a larger monitor and carefully double checking each image helps a lot. Patience and attention are key, especially as animals may appear tiny or partially obscured. When possible, it’s helpful to sort images into folders based on the animal’s common name (like red fox, mountain hare, or flat-headed vole) or even scientific name, if you are aware of it. There’s a reference guide to assist with many of the common species you'll encounter. And don’t worry — if you're unsure, even broad categories like “rodent”, “bird”, or “unknown” are perfectly fine and still incredibly valuable.

Please note: while sorting camera trap images is genuinely fun and rewarding, it’s important to treat the data with care and respect. These are sensitive research materials. Volunteers must not share images on social media unless explicitly permitted by the monitoring coordinator or research team. This protects the integrity of the research and, importantly, the safety of the animals being studied.

And speaking from my own personal experience — I can promise you’ll encounter some truly exciting surprises. The first time I received a batch of several hundred images, I curiously flipped through them. Many of the initial frames revealed serene, rocky mountain landscapes — stunning in their own right, but quiet in terms of wildlife. Then, on about my fifth image, I froze: there was a snow leopard staring directly into the camera! Flipping back, I realized this magnificent animal had been strolling right toward the camera, pausing briefly as if wondering, "What is this strange object?". Several other snow leopards appeared too, including one who closely inspected the camera, inadvertently taking hundreds of blurry selfies in the process. It was an electrifying moment for me — seeing wild snow leopards, one of my absolute favorite animals (next to manuls, of course!), genuinely took my breath away and sent a jolt of excitement through my body.

Moments like these more than compensate for the time spent scrolling through empty frames or wind-triggered images. Plus, there tend to be plenty of fascinating creatures popping up to keep things interesting. But don’t take my word for it — here’s a sneak peek at some remarkable camera trap images I’ve personally annotated so far (and yes, I have permission to share these 😸 ):

A snow leopard peering directly into the trail camera — a surprisingly common behavior for these intelligent, curious cats.

Another curious snow leopard, captured at night thanks to the trail camera’s infrared sensor.

A red fox (Vulpes vulpes) against the stunning snow-covered backdrop. Red foxes overlap parts of the manul’s range and likely compete with them for prey.

A group of ground-nesting Altai snowcocks, a common species in the Altai mountains — probably too big to be a menu item for manuls, but these plump birds make great meals for snow leopards.

A stone marten inspecting a trail camera placed opposite of the one taking these photos — another marten came up later to spray its scent directly on that camera.

A golden eagle, swooping in. A potential (if not likely) predator of manuls in these habitats.

Here’s a wolverine, which was an utterly unexpected and stunning sight for me.

And now, the moment I was really hoping for…

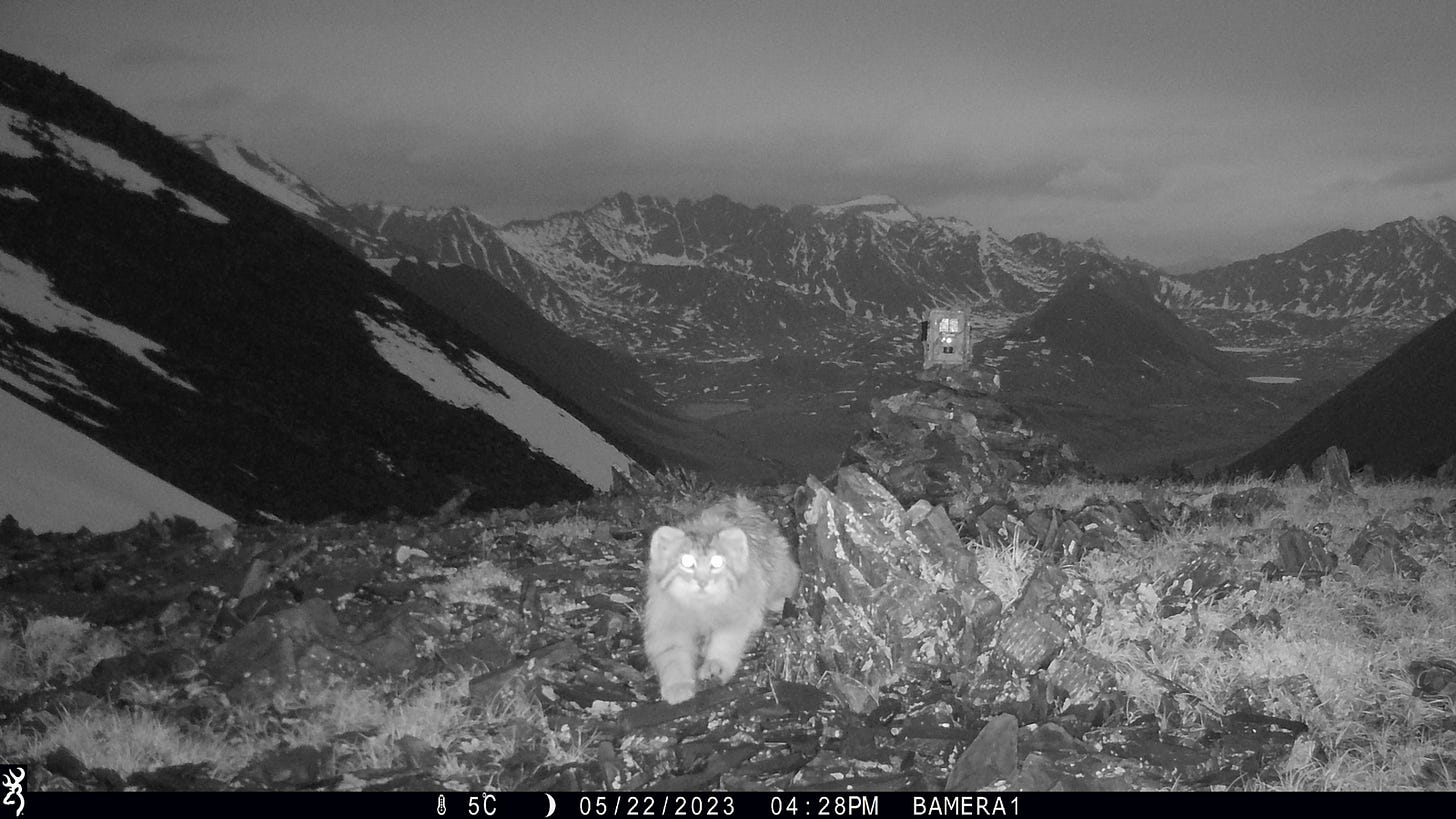

And at last — my first manul sighting! Manuls didn’t appear particularly common in this region during the year these trail cameras were deployed, at least not compared to their snow leopard cousins. This one was a bit soggy.

Another manul. If you look closely, you’ll see a particularly angry little face.

Together, these images paint a picture of a rugged and unforgiving landscape, full of extreme weather and a myriad of threats. They highlight the resilience of all the species that call these mountains home. But they also offer valuable clues into prey abundance, manul distribution, predator presence, and even behaviors.

It’s worth noting that these particular images — captured at high elevations where snow leopards roam — may not reflect typical manul habitat. In the Altai region, snow leopards are usually found in the upper nival zone, while manuls generally stick to lower elevations, such as the foothills and mid-mountain steppes. Historically, it was assumed manuls avoided these high-altitudes — which makes these manul sightings all the more exciting! These images from Sergey Spitsyn’s cameras (originally deployed to monitor snow leopards), may help clarify how, and when, manuls make use of these harsher highland areas.

If you’ve made it to the end and feel like this is something you’d enjoy helping with, I encourage you to sign up to volunteer with the Manul Working Group using this form. It’s a meaningful and fulfilling way to contribute to real conservation work — from the comfort of your own home! Finally, many thanks to Anna Barashkova of the Manul Working Group for sharing this opportunity with me and offering valuable insights that helped shape this article.

What a cool collection of images and a great opportunity. Altai looks stunning, and it's good to know that this sort of remote visit contributes to the science, too.