There’s a common name for my favorite short-legged felines — Pallas’s cat. Many of you know them by this name, but where does it come from? The answer lies with an 18th century German naturalist, Peter Simon Pallas, and an era in which people assume that scientists had a habit of naming species after themselves. (spoiler: Pallas didn’t name the cat after himself).

It all started in the 18th century, when Pallas trekked across Central Asia and Russia in search of natural curiosities. While revolution brewed across the Atlantic, Pallas was busy writing one of the first scientific descriptions of the strange, stout feline we now adore. In 1776, he officially published the species under the name Felis manul.

As our understanding of feline taxonomy evolved, zoologists realized that manuls weren’t actually part of the Felis genus (which contains small cats the likes of sand cats, black-footed cats, and European wildcats). In 1842, Johann Friedrich von Brandt reclassified them under an entirely new genus: Otocolobus, derived from Greek roots meaning “stunted ear” — a clear reference to their distinct, low-set, and rounded ear shape. The Greek kolobós (κολοβός) can be translated as “truncated”, “mutilated”, or “cut short”. So, despite what you may have heard, Otocolobus doesn’t actually mean “ugly-eared” —that’s a myth (or at the very least, a bit of a stretch).

While “Pallas’s cat” is the commonly accepted name in the West, Pallas himself never called them that. Instead, he recorded the local name — “manul” — a term likely originating from Mongolian (мануул) and still used in many parts of the species’ native range. Taxonomists of the time often borrowed indigenous names for newly described species, and Pallas was no exception. And he was well prepared, because unlike many of his contemporaries, he wasn’t just documenting plants and animals — he was also recording languages and ethnographies.

Pallas’s work was influential enough to earn him the reverence of Catherine the Great, who originally brought him to Russia as one of the empire’s leading scientists. His explorations took him deep into Siberia, across the Kazakh and Mongolian steppes, and beyond, where he documented not just the manul but many other species. His legacy in zoology extends far beyond the cat that now bears his name. Circling back — “Pallas’s cat” came later, when other scientists coined the name in his honor. And while many species now bear his name — Pallas’s gull, Pallas’s sandgrouse, Pallas’s leaf warbler, and Pallas’s glass lizard — let’s be honest, only one has truly achieved internet fame.

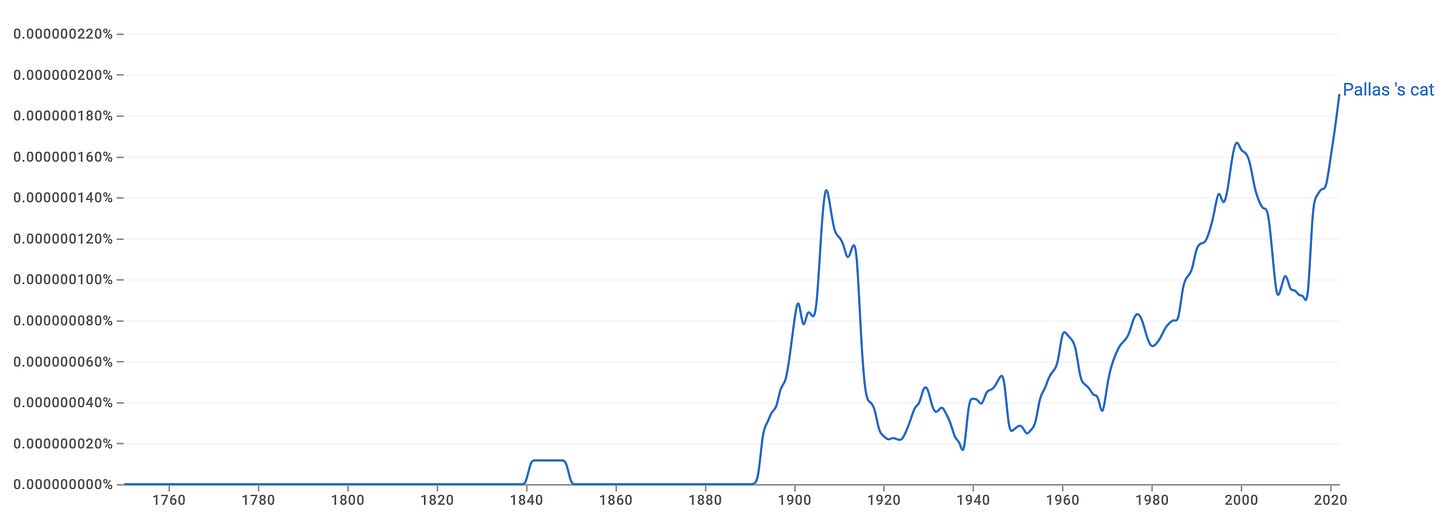

I thought it would be fun to look at the historical usage of “Pallas’s cat” in English literature using Google’s Ngram. It turns out, the name didn’t even come around until mid-19th century. By the 20th century, references to Pallas’s cats took off — with a sizable spike in the last decade or so, coinciding with their internet meme era.

Though, in regions where these cats actually roam, the name “Pallas’s cat” means little. Across the Central Asian steppe, herders and steppe dwellers call them manuls (or other variants originating from local languages). Which raises an interesting question: Does calling them by a Westernized name disconnect them from their native landscapes?

I think so. Names shape the way we see species. They might seem like a minor detail, but they influence public engagement, conservation funding, and even policy decisions. Using the indigenous name, manul, may seem like a small change — but it reinforces that these animals are not just specimens in the annals of zoology. They are a vital part of the landscapes they call home. As a manul enthusiast and nature lover, I can’t help but favor the original, indigenous name. After all, Peter Pallas didn’t “discover” the manul — he was just the first Westerner interested and affluent enough to publish a species description. Speaking of which…

Pallas’s own description

Interestingly, in the original description, Pallas noted that in Mongolian, the name is “Manul”, while in Russian it was “степная кошка” translating simply to “steppe cat”. The Latin text, admittedly difficult to read, compares the manul’s size to a fox (Vuples), while describing its large head, strong limbs, and Lynx-like appearance. Pallas was remarkably detailed in noting the species’ unique facial markings, including the black spots on the head, two oblique cheek lines extending from the eyes, and the distinctive six-ringed tail — three of which are darker and more pronounced toward the tip (though I should mention that tail ring counts vary among individuals).

Pallas may not have named the manul after himself, but he certainly saw something special in them. And centuries later, the internet seems to agree.

Pazi, I've been parroting the ugly-eared slander for a while now. I stand corrected! This was a great post.

I’ve read that they’re also called “dromba” in parts of the Tibet which I find to sound quite funny. Great newsletter please keep it up!!